This website and its associated repositories, are deprecated and no longer supported by the OSGi Alliance. Please visit https://enroute.osgi.org for the latest supported version of OSGi enRoute.

This enRoute v2 archive site is kept for those who do not intend to use the latest version of OSGi enRoute. If you are new to OSGi enRoute, then please start with the latest OSGi enRoute.

The Scheduler API was designed to be used in the following cases:

scheduler.after( ()-> foo(), 100 )scheduler.at( Instant.from( dateTime ) )scheduler.schedule( ()-> foo(), 10, 20 , 40, 100 )scheduler.schedule( () -> foo(), "10 10 10 FRI#3 JAN-JUN ?" )CancelablePromise<Integer> cp = scheduler.before( p, 100 )scheduler.after( C::work, 0)In general, you should use this service if your problems requires timing related functionality.

Basically the API replaces the java.util.Timer and java.util.concurrent.ScheduledExecutor while providing quite a bit more bang for the buck. It is bundle aware so that any schedules or delays are properly canceled when the bundle is stopped and implementations can throttle background tasks per bundle. It is also working together with the Promise to make asynchronous programming easier.

This section discusses the Scheduler API. The examples assume the following component:

@Component

public class SchedulerComponent {

Scheduler scheduler;

@Reference

void setScheduler(Scheduler scheduler) {

this.scheduler = scheduler;

}

}

The OSGi enRoute Examples repository holds the osgi.enroute.examples.scheduler.application application project. This application shows variations of all the calls and has a GUI to exercise the API.

The after(...) methods are used to schedule delays. For example, to execute a call after 10 seconds:

Promise<Instant> promise = scheduler.after( 10000 );

promise.onResolve( () -> System.out.println("Result " + promise.getValue() );

This was the most simple version of the after methods, it returns a promise that is resolved with the Instant at resolve time. It is also possible to provide a Callable<T> that will be executed after the timeout. In this variation the promise will be resolved with the return value of the callable (or failed with the Exception).

Promise<Integer> promise = scheduler.after( () -> return 1, 10000 );

promise.onResolve( (p) -> System.out.println("Result " + p.getValue() );

To make life easier, there are also convenience variations that take a java.time.Duration:

Duration duration = Duration.ofSeconds(10);

Promise<Instant> promise = scheduler.after(duration);

The after methods will schedule the event in the background (they are never executed on the same thread). Specifying a delay that is less than 0 will schedule the event immediately. You can therefore also use the after methods to off load the current thread.

If you want to do something at a specific time then the at methods are your friends. The are convience methods since they in general will calculate the delay from the current time to the scheduled time.The simplest is of course executing at a given instant time:

String parameter = "2015-01-13T09:54:42.820Z";

LocalDateTime localDateTime = LocalDateTime.parse(parameter, ISODATE);

ZonedDateTime zonedDateTime = localDateTime.atZone(ZoneId.of("UTC"));

Instant instant = zonedDateTime.toInstant();

Promise<Instant> promise = scheduler.at(instant);

promise.onResolve( () -> System.out.println("Yes!") );

The actual return values of the after methods are not Promise but CancellablePromise. This is a subtype of Promise’ to add a cancel() method. There is of course a race condition between the cancel and the event. The cancel method returns a boolean. If this boolean is true, then the event was canceled and will never be executed. If it returns false it means the event was already executed or was already executing when the cancel method was called.

CancellablePromise<Instant> promise = scheduler.after( Duration.ofSeconds(10) );

assert promise.cancel() == true; // cannot have been executed yet

assert promise.getFailure() == CancelException.SINGLETON;

promise.then( (p) -> {

System.out.println("Hmm, we should have failed this one");

return null;

}, (p) -> System.out.println("Happy with failure!" );

Promises are wonderful little creatures but sometimes you need to time them out. Unfortunately, the freshness of certain results are just not what they used to be so after a certain amount of time they become useless. This function is provided with the before() method. This method returns a Cancellable Promise that will be canceled with a Timeout Exception (which is also a singleton) when the given timeout has expired.

Instant start = Instant.now();

Promise<Integer> target = scheduler.at( 10000 );

CancellablePromise<Void> before = scheduler.before(promise, 1000);

before.then(null, (p) ->

assert p.getFailure() == TimeoutException.SINGLETON;

);

The next step is to have a repeated event. For example, you need to check a sensor every 5 seconds or do some other polling. The simplest form is the fixed schedule. It takes a number of timeouts and will repeat the last timeout until the schedule is closed. For example:

Closeable schedule = scheduler.schedule(

()-> System.out.println("tick!"), 100, 200, 300, 400 );

scheduler.after( schedule::close, 5000);

The example will first fire the event after 100 ms, then will delay 200 ms, do the event, delay 300 ms, do the event and then repeat the 400 ms delay. In the example we close the schedule after 5 seconds.

If a bundle stops (or the Scheduler service is unget) then any schedules created by that service will also be closed.

We’ve now reached the flag ship of the Scheduler. Until now it almost looked like time was not that hard. Any developer that tried to create real world schedules based on calendars knows how mind boggling complex date and time can be. Want to run every Wednesday? Or only on the last Friday of the month? Tricky. In Unix they had cron jobs since the dawn of time (for computer scientists time starts Jan 1 1970). A cron job had a specification and some task to execute. One of the great innovations of the Java world is that we improved over these old fashioned Unix cron expressions by adding seconds at the start of the expression. Quartz has been a popular product providing cron expression to our beloved Java world. We largely follow them except that day numbers for the Java 8 convention.

In principle, it had a number of space separated fields, where each field had an assertion on a chronological unit. That is, the first column specified an assertion on the minutes of the hour, the second the hours in a day, and then it became more complicated because a day can be asserted relative to the week or the month or the year. Ah well, time …

These assertions were basically a constraint on the number, where the number represents the seconds, minutes, etc. The simplest assertions is the wildcard, signified by the easy to remember asterisk (‘*’). For example, the following cron expression will run every second:

* * * * * ?

If we prefer to run every minute, we clamp the seconds:

0 * * * * ?

We could also want to run at every 5th second, this is specified with a solidus (also known as slash ‘/’) followed by the repeat value. The following schedule runs every 5th second.

0/5 * * * * ?

We can also limit the times the schedule runs by a range. This range then describes the period in which events can take place. For example, if you have the crazy idea to run every 5 seconds for the first 30 seconds of every minute then you could leverage the following expression:

0-30/5 * * * * ?

This is of course terribly inflexible, just imagine you also want to run between the 45th and 55th second of every minute! And of course not that boring 5 second interval, we need 3 seconds! The developers budged and you can use the conjunction operator (‘,’) to or different assertions together.

0-30/5,45-55/3 * * * * ?

It should be clear that you will have to dig pretty deep to find any reason to be indignant about missing functionality. So let’s move on. The assertions should be pretty clear, but we have to start talking about days. After the hours, you can specify a day in the month number. For example, we want to run on the third of each month:

0 0 0 3 * ?

Obviously, the beginning of the month is easy, but how do you specify the last day of the month? Well, we’ve got you! You can specify the ‘L’ instead of a number, this signifies the last day of the month.

0 0 0 L * * ?

Yeah, you now probably are looking for finding holes, imagine I only want it on weekdays? Got you covered buddy! If you suffix the ‘L’ (or a day in month number) with a ‘W” then we’ll find the nearest weekday in the same month:

0 0 0 15W * * ?

Ok, understand your mind is now racing and undoubtedly you want to run on the third Sunday of the month. You can do this by postfixing the day name or number, a hash, and the number of the week in the month.

0 0 0 SUN#3 * ?

Let’s move on to the month. The month is between 1 and 12 as you might expect. For good grace, we threw in the English 3 letter month names (JAN, FEB, MAR, APR, MAY, JUN, JUL, AUG, SEP, OCT, NOV, DEC). Don’t let this withhold you from some creative expressions like:

0 0 0 15W 1,MAY,OCT-DEC ?

Now we get to the part that was nagging you all along, the question mark? Well, the position of this question mark is for the day of the week. It is a question mark because if we specify the day of the month we should not specify the day of the week and vice versa. So if we want to specify the day of the week, we better make the day of the month a question mark. For example, we want to run on every Sunday:

0 0 0 ? * SUN

And if you have the weird idea to run on the last Sunday of the month, we graciously give you the ‘L’ again:

0 0 0 ? * SUNL

Time to close this down. There is one optional part not appearing: the year. If you want to restrict a schedule to a number of years then you can suffix the year assertion:

0 0 0 ? JAN MON#1 2000-2022

So assuming your highly impressed of this cron expression syntax, how do we use it? Well, we have a method for that:

String cron = "0 0 0 ? JAN MON#1 2000-2022";

Closeable close = scheduler.schedule( () -> Shouldn't you be kissing your partner????"), cron );

Don’t forget to run this every December just before new year. Otherwise it will be a long wait.

Since your convenience is our goal, we’ve added a number of shortcuts for common schedules:

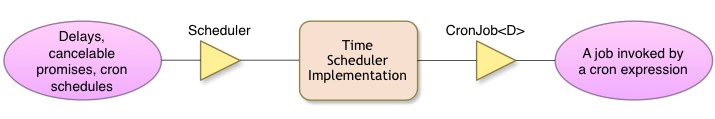

@reboot – Every time the system is started@yearly – Once a year on Jan 1@monthly – Once every month on the first@weekly – Once every week on Sunday@daily – Once every day@hourly – Once every hourUsing the scheduler is good, not using the scheduler is even better! That is why the OSGi Alliance invented the whiteboard pattern. It is often much easier to just register a service and wait to be called. Scheduler, being a good OSGi citizen, supports this model. It will track any Cron Job services that have a cron service property and call the Cron Job at the appropriate times.

@Component( property=CronJob.CRON+"=0 0 0 ? JAN MON#1 2000-2022"

public class ExampleCron implements CronJob<Object> {

public void run(Object object) throws Exception {

System.out.println("Yes, I am so happy to be discovered");

}

}

You know of course that you can use Configuration Admin to set the service properties, so you can override the default scheduler with something more suitable.

But what about that Object parameter? Well, we have not told you yet that you can actually prefix the cron expression with properties. The parser for the cron expression only parses the last line and treats any preceding lines as properties. If you specify and interface then the scheduler will create a proxy on that interface and use the interface’s method names as the names of the property. For example:

interface Foo {

long telephone();

}

@Component( property= "telephone=0633982260\n"

+CronJob.CRON+"=0 0 0 ? JAN MON#1 2000-2022"

public class ExampleCron implements CronJob<Object> {

public void run(Foo foo) throws Exception {

System.out.println("Glad you called " foo.telephone());

}

}

The scheduler will pick up the interface from the properties from the generic information in the types. This unfortunately does not work for Java 8 lambdas, they mysteriously ignore the generic information. If you’re using Declarative Services to register the service then you’re ok.

You can find an example project with scheduler examples at osgi.enroute.examples. This is an application you should run in the debugger so you can trace what happens.