This website and its associated repositories, are deprecated and no longer supported by the OSGi Alliance. Please visit https://enroute.osgi.org for the latest supported version of OSGi enRoute.

This enRoute v2 archive site is kept for those who do not intend to use the latest version of OSGi enRoute. If you are new to OSGi enRoute, then please start with the latest OSGi enRoute.

There are a number of patterns used in OSGi systems.

The Service Whiteboard pattern is useful when you need to register with a server (for example to get events) but the absence of that other party does not prevent you from making progress. A typical example is listening to changes in the configuration entries in the Configuration Admin service. The Configuration Admin service should dispatch these to any Configuration Listeners service. However, a Configuration Listener can run perfectly happy before there is a Configuration Admin service around. And since the Configuration Admin can run before any Configuration Listener service are registered, the life cycles of the Configuration Admin service and the Configuration Listener service are completely decoupled.

Most OSGi Services, except the first few, are designed according to the whiteboard pattern.

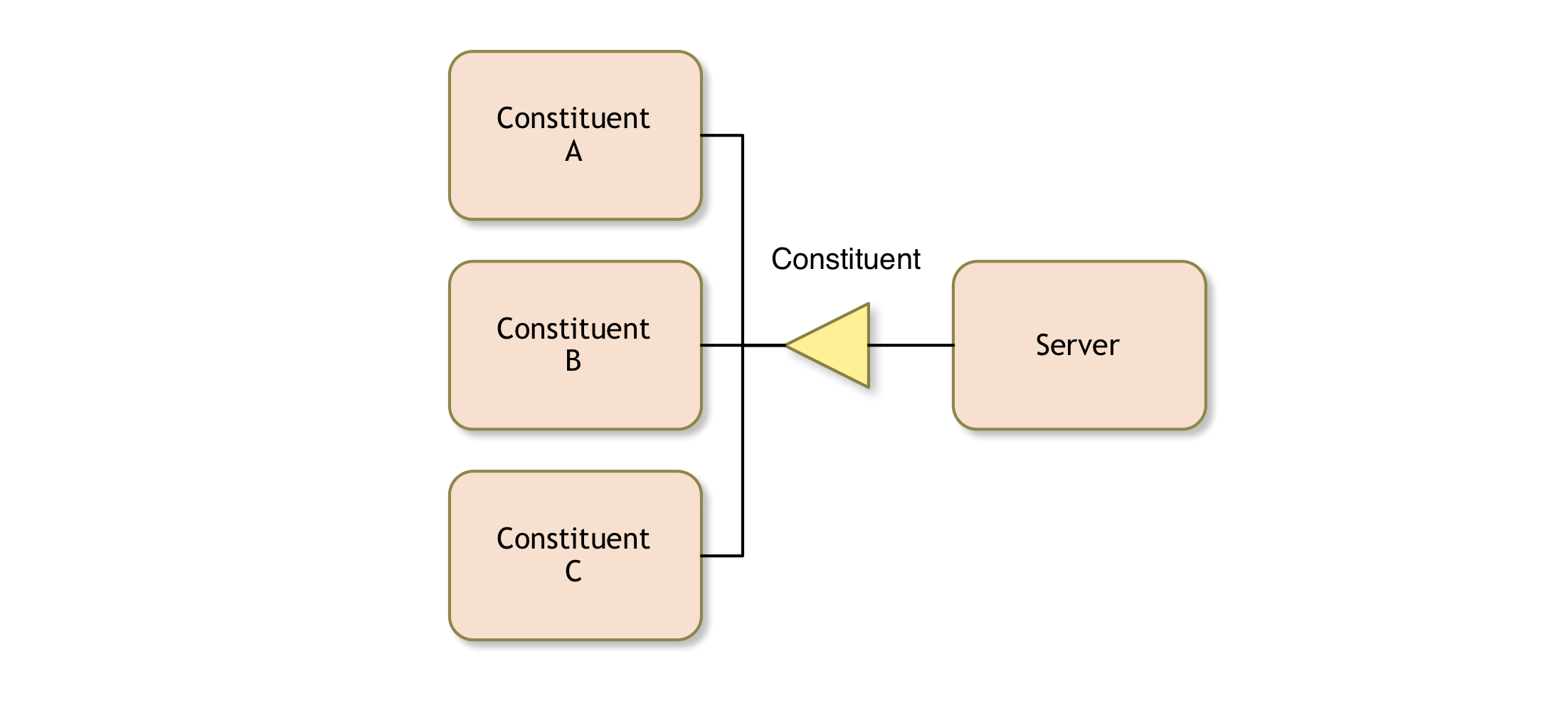

The whiteboard pattern is defined as a server that uses the OSGi service registry to find its constituents, where each constituent is registered as a service. A constituent can for example be like a traditional listener. This is in contrast with a pattern where the server registers itself as a service and the constituents then register with this server service.

The whiteboard pattern is used when different actors collaborate. In a collaboration model there are multiple parties that interact and need to exchange information at appropriate times. In general, this interaction goes into a certain direction. For example, in Event Admin, the direction is from a sender to a handler. The sender depends on the Event Admin service: it needs the Event Admin interface to send or post an event. In a more traditional ‘listener’ model, the handler would have to be explicitly registered with the Event Admin service. In this vein, the handler would also depend on the Event Admin service: it would need the Event Admin interface to add itself as listener. In the Whiteboard model, the handler doesn’t register itself as a listener to the Event Admin service (as a consequence, the handler does not depend on the Event Admin service). Instead, the handler is directly published in the service registry, and the Event Admin service tracks the published handlers.

In an OSGi system the ‘listener’ model is not recommended because it is more work, it has many potential problems in a dynamic world, and the service registry is a much more powerful and robust (concurrent) mechanism to handle these ‘listeners’ than that what most providers are willing to provide as registry. And last but not least, there is a free introspection API that is used by all OSGi debugging tools.

Using the service registry allows the use of service properties to provide meta data for the service. For example, in Event Admin an Event Handler specifies the topic and filter as service properties. These are picked up by the Event Admin implementation and used to filter the events that are sent to the handler.

The following is an overview of where the Whiteboard Pattern is used in the OSGi services:

Novice OSGi users often feel uncomfortable publicly registering these listeners. There are performance fears and a feeling of being unprotected. Performance is not an issue since there have been tests with hundreds of thousands of services without any noticeable degradation. The feeling of being vulnerable will go away once you see how the services in a service registry are collaborating.

Clearly the pattern is common and popular because is so easy to implement. Virtually all OSGi services after release 1 are based on this model. On any occasion where you want to establish a channel of eventlike objects, the whiteboard pattern should be used.

This example shows a skeleton of a service that listens to a whiteboard service.

package com.acme.server;

@Component

public class TickerImpl{

@Reference(policy=DYNAMIC)

final List<Tick> ticks = new CopyOnWriteArrayList<>();

private Closeable schedule;

@Reference

void setScheduler( Scheduler scheduler ) {

schedule = scheduler.schedule( () -> {

ticks.stream().forEach( t -> t.tick() );

}, 1000);

}

}

package com.acme.client;

@Component

public class TickWhiteboardImpl implements Tick {

public void tick() {

System.out.println("I am here!");

}

}

The Extender Pattern is useful when you find that bundles have to repeat the same boilerplate code or resources to function.

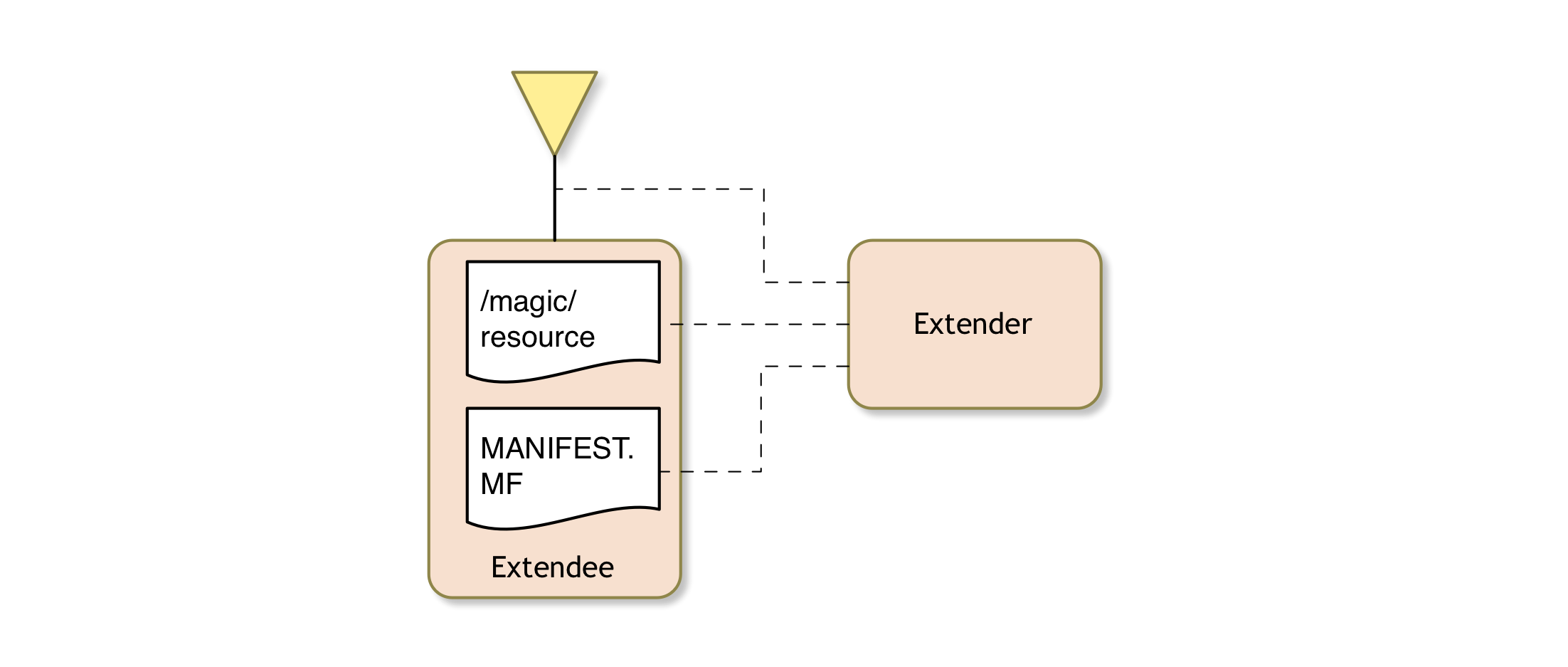

With the Extender Pattern, the bundles only provide the unique part and any shared/common parts are provided by another, shared, bundle. The extender is the bundle that operates on behalf of an extendee, the bundle that contains the unique parts. Extenders generally define a manifest header or magic directory to allow an extendee to opt-in.

For example, the Declarative Services specification defines an extender model. A component provides an XML file inside its bundle (generated by the annotations) that is read by the extender bundle when the component bundle gets started. This extender bundle then does all the boilerplate code to register services, check dependencies, handler configuration, and many tasks you don’t want to know about.

The benefit is that the extender allows a ‘declarative’ model, which usually leads to smaller and more concise extendees.

The extender model works in OSGi because the bundle life cycle is well defined and evented. An extender bundle can listen to the installation of a new bundle as well detect that bundles are/have been uninstalled. It can therefore actively scope its utility around the life cycle of the extendee. For example, Declarative Services will wait to activate components until their bundles’ are started.

One of the primary goals of the extender pattern is to allow bundles to be self contained. A hard problem in system deployment is that systems consist often of so many parts that can reside in quite a few places. Orchestrating all these parts is surprisingly difficult. Not just during an install, also during the uninstall of a module. Having a unified deployment artifact for code, resources, and configuration therefore simplifies the deployment phase.

Bundles are excellent artifacts for virtually anything that can be represented as a resource/file since they are based on the ZIP format with a manifest. What the purpose is of a particular resource is in the eye of the beholder. Class files are code, but this is an interpretation of the VM. A manifest is paramount for OSGi but is interpreted by the framework. The VM and the OSGi framework are given, however, their strategy to look inside the ZIP file to find things they know can easily be extended in an OSGi system by allowing all bundles to look inside any other bundle. Since the framework sends out events when the life cycle state of a bundle changes, it is quite easy to track the state of other bundles. (The Bundle Tracker actually makes this trivial.)

The following OSGi service specifications are extenders: