This website and its associated repositories, are deprecated and no longer supported by the OSGi Alliance. Please visit https://enroute.osgi.org for the latest supported version of OSGi enRoute.

This enRoute v2 archive site is kept for those who do not intend to use the latest version of OSGi enRoute. If you are new to OSGi enRoute, then please start with the latest OSGi enRoute.

In the last releases of OSGi specifications Data Transfer Objects (DTOs) have become quite important. This comes as a surprise to people because DTO’s are very non-object oriented and wasn’t object oriented a euphemism for good? DTOs give up some of the benefits of object-oriented programming to avoid the horrid problems associated object serialization in strongly typed languages.

This Application note discusses the background of DTOs and attempts to explain why they are so important in modern systems.

Objects came to life in the eighties of the previous century and provided many advantages over its predecessor, structured programming. It provided an organizing principle for larger software systems by hiding data and accessing this data with functions (methods). Though its start was very rocky it became main stream in the late nineties and is now solidly established as the best practice for software. The Java language was the culmination of object oriented thinking.

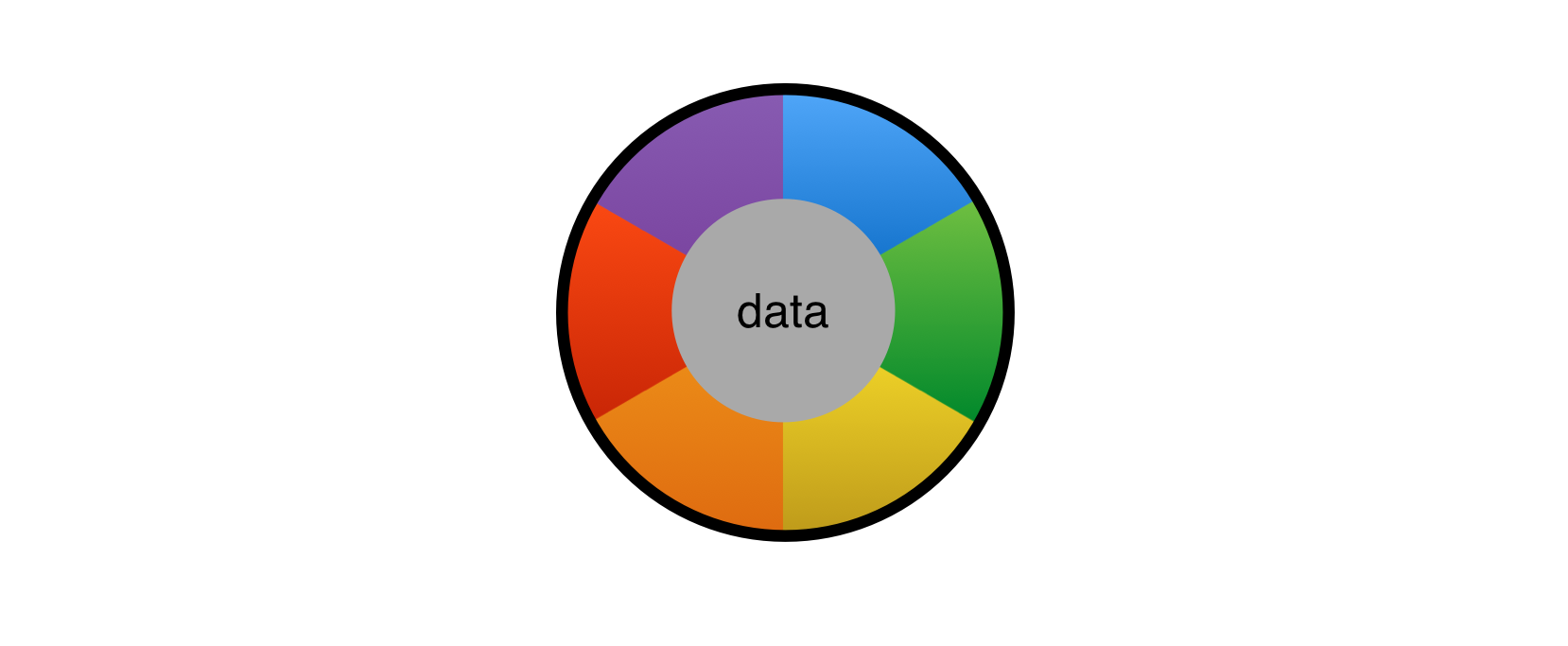

This thinking also gave us Java beans. These were basically place holders for data but could

only be accessed via methods that followed a strict (quite complicated) naming pattern. That is a getX

method would represent the getter of an x property. Beans seemed to provide protection against evolution of the code base

because the data was shielded, one could only access it via a method. If the data changed, other code could be kept because the

methods could convert the different internal structure in a backward compatible way. In the following picture we show by having the data (grey)

shielded by the methods (the other colors).

Undeniably this works well in a single process. There was just one caveat, there are no single process programs anymore. I assume this previous sentence will raise some eyebrows because quite often people are not aware that any process that talks to a database is multi-process. An embedded database will not save you because it is not the database process that is the other process. It is your process that is the other process. Anytime you store data you do that so that at another time you can read that data again. Over time this is highly likely another process and then there is the inevitable moment that you update your application. Suddenly you must be acutely aware that the access methods that you so painstakingly wrote are not shielding you at all.

Your object’s private fields are public API once they escape the process…

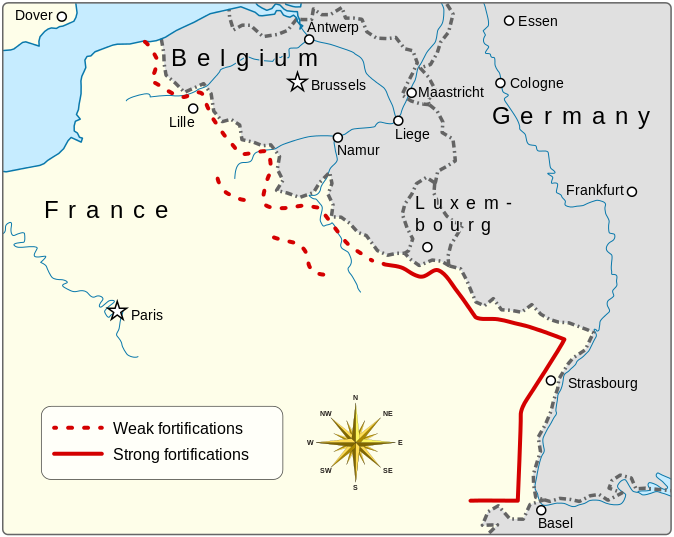

Methods to shield your data is a bit like the Maginot line. Before World War II the French built a fortress all along the frontier with Germany at quite unbelievable cost. It even had munition trains deep underground. The Maginot line was clearly unbeatable though this was never proven because the Germans just decided to sneakily walk around it.

Beans, it turns out, have the software version of the strong and weak fortifications of the Maginot line.

The same problem happens when you transfer a message to another process. You can rarely control that the receiver and the sender are actually compatible on their private fields. The answer to this is to create an intermediate representation. IDL from Corba, Protocol buffers, ASN.1, XML Schema, JSON, the list of solutions to this problem is surprisingly long.

Once you realize that you need to maintain an external representation of your data the question is raised: do I need an internal representation as well? Any semantic or type difference between the external and internal representation is extremely painful because it forces you to mediate every time when you need to convert one to the other. This is always the dumbest, error prone, and most boring code to write. Automating it is paramount but handling the evolution of your schemas is often quite painful with automated tooling.

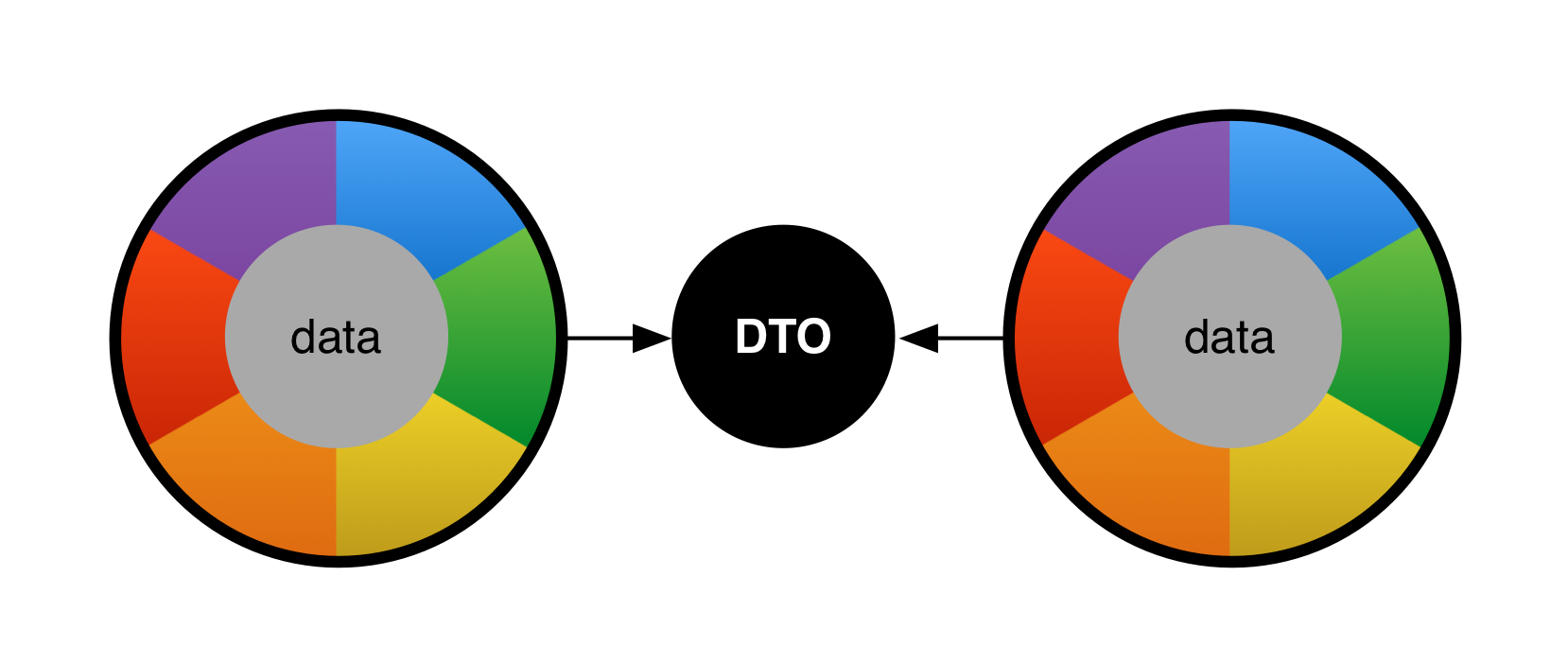

Since your external representation must carefully evolve in a backward compatible way why not use it internally? Having a single representation makes the code a lot simpler (and more fun) to write and removes a surprising range of error cases. However, it profoundly changes the object oriented design model. Instead of having the data private, it is now fully exposed and completely different objects now provide behavior on this well defined data object. Though we now must carefully evolve the data types over time, we now have the advantage that we can use the same data in different places, even in different processes and potentially different languages. This is shown in the following picture.

This is demonstrated by Javascript and other dynamic language. If you work in Javascript then you’re very familiar with JavaScript Object Notation (JSON). One of the great joys of Javascript is that you rarely need to write those mediating functions because JSON objects are just data. This is partly caused by the (very) relaxed type system but mostly because the data is method free. What you see is what you get.

This is the primary reason for DTOs. DTOs are ‘naked’ data. Because of this simplification, we can use the Java language to specify our external representation, just like Corba’s IDL, JSON, XML Schema, or Protocol Buffers do. These DTO’s can be trivially send to other processes. The severe constraints on DTOs makes them very simple. Because they are so simple, it is a lot easier to provide independent functions that can manipulate a DTO or any DTO. Actually, DTOs can directly be used as the type safe specification for JSON objects. Many other schema languages can be supported with specific annotations.

The first time the OSGi started using DTOs was after we had done the JMX work and started to provide a JSON interface for managing the framework. It became painfully clear that both JMX and JSON shared the identical data, only the form was different. We therefore decided to use DTOs as a specification and then map from the DTOs to the different management standards.

Around that time it also became clear that more and more systems were clustered or part of a larger whole. The Remote Service Admin specification captured this with a distributed OSGi model, where services can be exported and imported to and from communication endpoints. This trend fundamentally changed the way we started to think about services. If you look at the older services then it is clear that these services are not well suited for distributed OSGi. These services were designed with the best object oriented practices in mind. For example, Configuration Admin API is almost impossible to distribute because its Configuration Admin service returns a Configuration objects that would require a proxy so that each method call on that Configuration object would have to traverse the communications channel, which would be quite expensive if at all possible. If the Configuration object had been a DTO the API would have been a lot easier to distribute.

The current micro-services and (REST) API trend is very much a symptom of the same underlying problem that systems have become distributed and we better prepare for it. In OSGi, services are just objects but distributed OSGi has had a profound impact on the way we design services. Modern service APIs today should take the issues of distribution into account or risk being left behind.

The implication that data and behavior should be separated is often hard to swallow for people that have grown up with objects because it flies against everything they were being taught. Most people accept the primary problem that in many serialization schemes your methods don’t shield you. However, they still find it very hard to accept that the consequence is that the shielding methods become busy-work. But they have, and they uselessness is amplified by the developments in tooling. When objects were germinating in the eighties we did not have powerful typed languages, IDEs, nor refactoring. Shielding our data made sense because we did not get a clear error when a change was bad, nor could we easily rename types, fields, and methods through the whole code base. Today we do have those tools so we’re actually pretty well protected from a lot of the changes that the shielding methods protected us against.

That said, don’t turn every object into a DTO because objects and their methods do provide a tremendous benefit for objects that do have behavior. DTOs are only useful when you have to communicate them to another process.

If you know C then a DTO is a struct. If you don’t know C then a DTO is an object without methods, it is pure data. In Java it is implemented with a public (static) class that has only public instance fields with limited types and a public no-argument constructor. For example:

public class BundleDTO extends DTO {

public long id;

public long lastModified;

public int state;

public String symbolicName;

public String version;

}

In the OSGi DTO specification the set of types that can be used in DTOs is limited:

T ::= dto | primitives | String | array | map | list

primitives ::= byte | char | short | int | long | float | double

list ::= ? extends Collection<T>

map ::= ? extends Map<String,T>

dto ::= <>

The DTO class has some very specific requirements:

The OSGi DTO class has no equals nor a hashCode method. This makes them unsuitable as keys or for use in sets. The reason is that it is not the

data (the DTO) that defines what is the primary key of the data, it is the actual usage scenario that defines the fields of interest.

That is, one object can use the id field of the object as primary key but another object tracks by symbolicName and version.

You will therefore often find that DTOs are the values in maps but never a key. One field is then the key.

It is rare but allowed to add equals and hashCode methods.

In an object oriented design we create an API where all the objects have their own behavior. For services that can be distributed there are some concerns that should be taken into account.

In general, you want your service to be transactional. This means that instead of getting an object and calling methods on it, you want the service to deliver a DTO. If you need to modify data then you want to present a DTO with all the data to the service.

Realize that DTOs are cheap in two dimensions. The classes for the DTOs are simple and cheap and copies are cheap as well since most constituents of a DTO are immutable. Never return the actual objects to other modules, always make copies unless you know that the caller will not modify the object. One such case is the OSGi enRoute REST API that turns the return objects only to JSON so it will never change the actual object.

Traditionally JSON objects were constructed from String keys defined as constants in a map. Constructing such objects is very awkward and hard to read. DTOs resemble Javascript objects a.k.a hashes. This makes it trivial to turn a DTO into a JSON stream or vice versa. DTOs have one huge advantage over Javascript objects and that is that they are typed. JSON converters, like the one in the DTOs service, can leverage the type information when deserializing, including generic type information.

Interacting with a browser makes it clear why DTOs are so powerful. A lot of the Javascript envy disappears when you can toss DTOs around as easy as Javascript objets. And all that with the full support of the IDE and the type safe language. For example, in Java you can click on a field and ask who references it, something that is impossible to do right in Javascript. (OK, Intellij is doing a decent job.)

For example, the OSGi enRoute REST service was designed with DTOs in mind. This is all you have to write (really, no further setup) to create a REST API on /rest/bundle/:id.

@Component

public class MyManager implements REST {

BundleContext context;

@Activate

void activate(BundleContext context) {

this.context = context;

}

public List<BundleDTO> getBundle() {

return Stream.of(context.getBundles())

.map( this::toDTO )

.collect(Collectors.toList());

}

public BundleDTO getBundle(long id) {

return toDTO(context.getBundle(id));

}

BundleDTO toDTO( Bundle b) {

return b.adapt( BundleDTO.class );

}

}

OSGi enRoute includes the DTOs service. This service is very useful in working with DTOs. It provides the following features:

The OSGi enRoute DTOs service inspired RFP 169 Object Conversion, which resulted in RFC 215 Object Conversion. It is very likely that OSGi R7 contains this service.

The ease with which dynamic languages like Javascript can transfer data between processes is very hard to achieve with Java because its type safety. Many attempts to achieve a similar model don’t work very well in Java and often loose the advantages of type safety. Beans tried to provide a model where you had type safety and dynamic access but required a lot of boiler plate code that still fell short once one had to serialize the data.

The DTO is a very elegant compromise. It allows the Java code to leverage its powerful type system, letting the IDE to its awesome job.

The biggest disadvantage of the DTO is that it seems to violate a basic tenet of Object Oriented Programming. Since the majority of developers grew up with objects this requires a paradigm shift that is often difficult to achieve.